When metaphors met the mind

Human minds are instinctive. What more, they can draw insights from one experience, stored ready as a reference for some other moments coming up. On a sultry day, your mind kicks in to switch on the fan or air conditioner so you can alleviate the heat. This behavior was transformed into a lesson for some other application as well—the cooling of machines. Fan was considered as an outlet for the flow of air such that humans were able to visualize how these fans can not only help cope up with the heat inside a room, but also within appliances and devices. Hence came in cooling pads for laptops, built-in fans within systems, air conditioning for server rooms, and so on.

Well, this is just one grain in the bowl. Thinking back, we humans have applied certain learnings through observation into visualizing a lot many things of futuristic significance. The heydays of metaphor! For linguistic fanatics, this word ain’t new—it’s the figure of speech that has the ability to point to something while literally meaning another thing—both sharing the same essence. Through the etymological journey, the word ‘metaphor’ by itself has traveled through relatable meanings—from 16th century French ‘métaphore’ to Latin’s ‘metaphora’, finally bringing out the crux for ‘carrying over.’ The human mind is a living example of metaphors—carrying over the implications and factual knowledge of something and producing radical outcomes such as new ideas, inventions, and occasions.

Put simply, the mind has the power to indulge you into alternative thinking, if you can acknowledge and take notice of things that impact on you. Hard to believe? Most of the complex and enjoyable innovations of today are a result of everyday metaphors that some minds were able to capture and project. Not just with products or mechanisms, this kind of a metaphorical thinking can help boost your thought-process, showing its way into effectual writing, reading, cooking, and a lot others. So if you think it’s only about building products, think broader—everything is about building experiences, and metaphors guide us in this path.

There’s a saying that goes, “what works for you may not work for someone else.” Well, this certainly holds true in some cases, but most often, a twist to this adage is what metaphorical experiences are. Yes, what works for you at one thing can in turn have undiscovered applications in ten other things, which may impact on the lives of many others. Steve Jobs is known for his idiosyncratic behaviors, but this is one interesting life lesson he learned as a youngster would help him later build the iconic Macintosh. A young Jobs with the father Jobs was busy fencing in the backyard of their house in Mountain View, when the father said,

“You’ve got to make the back of the fence, that nobody will see, just as good looking as the front of the fence.”

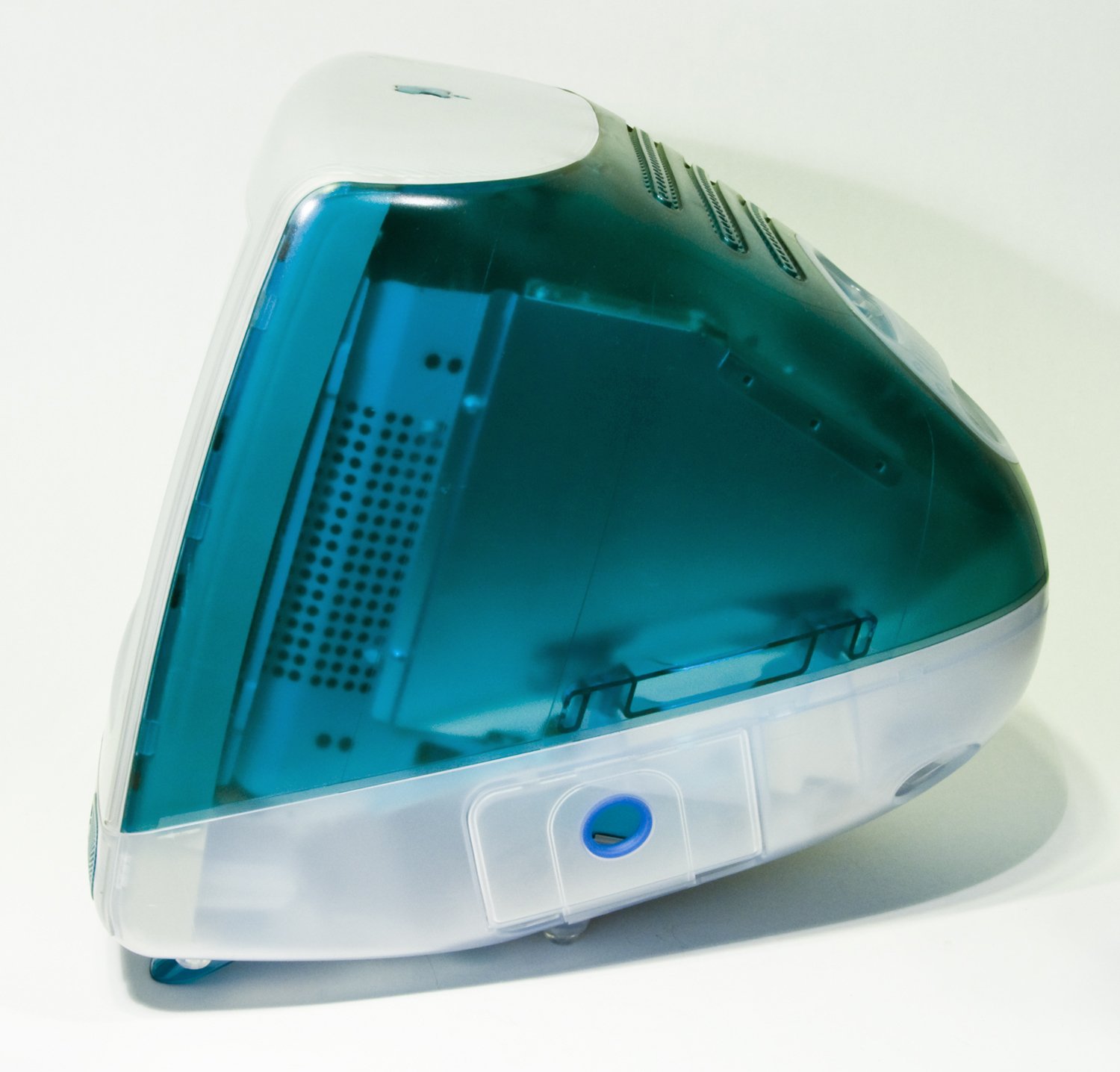

Great, definitely a good lesson for tidying up backyards, but did it stay only there? Jobs’ attention to detail to his father’s advice caught him at the right time when the Apple team was working on the circuit boards for Macintosh. Just because the inside of the computer was unseen, it doesn’t mean it has to remain cluttered. Jobs ensured the arrangement inside was just as stellar as outside, and ended up engraving on the board the signatures of the early engineers who worked on the product. How cool! Even the famous Bondi blue iMac’s back-casing relied completely on this fencing lesson—never leave the back of the machine clumsy with wiring running haphazard, just exactly like how every other computer company had it then. iMac’s design (by Jonathan Ive) was entirely based on a translucent Bondi blue back-casing, that shows the intricate wiring and circuit boards, still in an elegant manner. Fencing experience met computing finally.

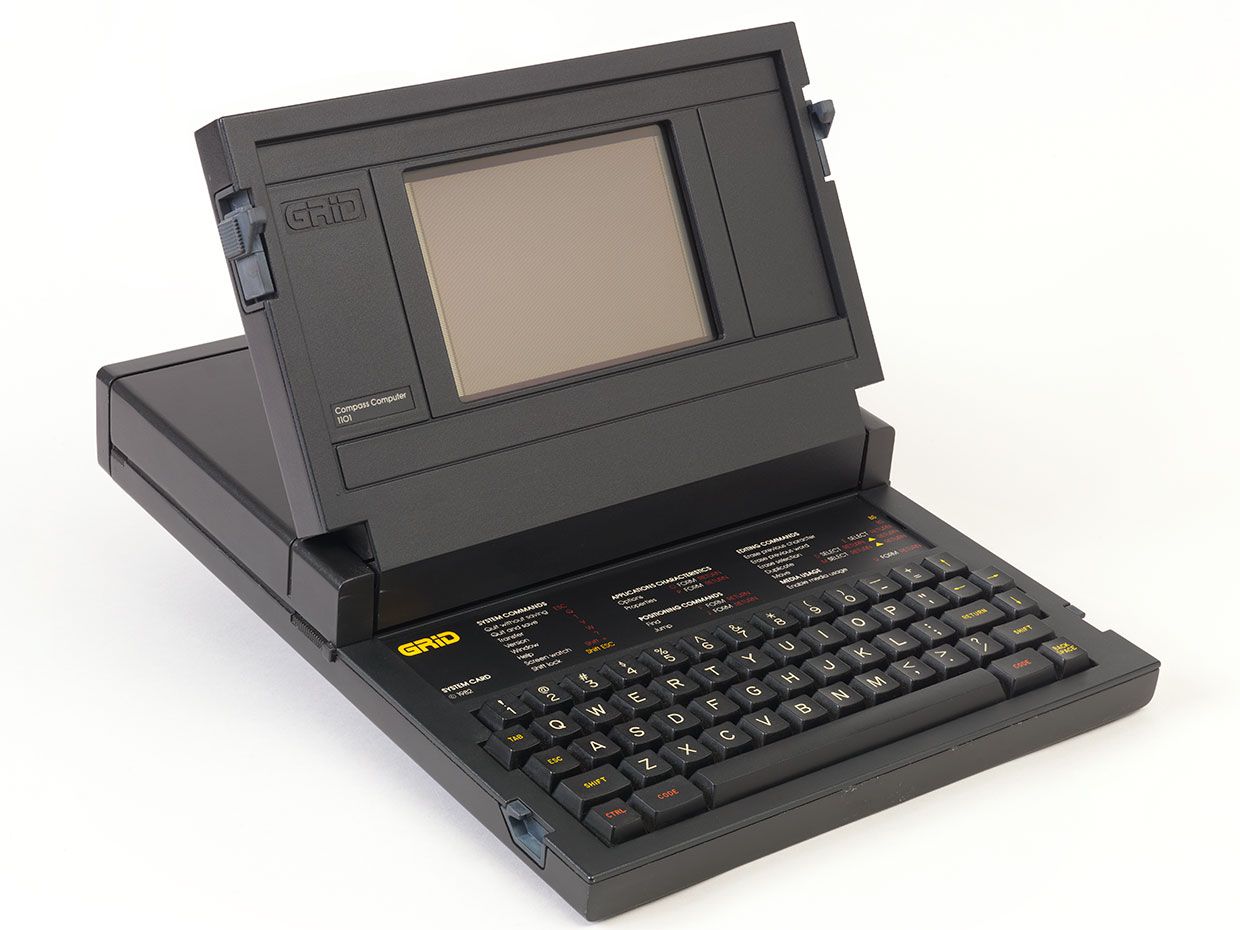

Humans consciously and subconsciously do a lot of actions, thanks to the mental models that get formed with every experiential journey we go through. And, these mental models are activated and presented not just when the same action happens again, but also when a parallel, relevant behavior is noted. It’s not what humans do, but what drives them to take the action, and how that gets carried over to similar instances. In a recent book I read, Cliff Kuang goes on to explain the early history of the first foldable computer aka today’s ubiquitous laptops. Bill Moggridge, one of the founding members of the renowned design firm IDEO was tasked with the job of designing the then first model of portable computer. Moggridge is said to have walked around always, carrying the individual heavy computer parts on this briefcase, and trying to assemble in multiple ways only to be disappointed with the overall structure and the non-lightweight prototype he ended with. When he was figuring out on what could be a best way to bring in the ‘portableness’ to this humongous setup, he glanced at the briefcase that he used to carry—the opening and closing and the easy pickup-and-drop. Tada! Came the idea for GRiD Compass, the first-ever laptop, with foldable clamshell mechanism that was imprinted already in our minds, thanks to our briefcases. An excellent example of metaphor, right?

Most of the metaphors aren’t specially quoted or raved about until people get to catch them in action personally. In one of my previous articles about psychological nudges in products, I’d have discussed how Kindle preserved the look, feel, and mechanism of an actual paperback—predominantly the reason for many bibliophiles to try it out in the first place. In fact, people could appreciate this metaphor-to-real-book only when they subconsciously turned the page or even looked at the electronic ink technology that gave a paper-like screen.

Tech apart, this metaphorical take when applied to our personal thinking helps in appreciating, learning in depth about occurrences, bringing clarity to thoughts, and portraying experiences. Exactly why we appreciate Wordsworth’s poems and Ruskin Bond’s stories—they bring nature to life with their metaphorical comparison to everyday lives.

So how do these metaphors exist and how do we tap into them? Even so, how do metaphors help us in the longer run?

Pause and rethink

The least appreciated action is ‘pause’ because it always tends to carry a negative connotation to it. But, occasional pausing or slowing down of our mental processing can help see even lacklustre events with logic (well, exceptions definitely included). This essay is a testament to rethinking that comes after a brief pausing—my points on how human minds can connect occurrences remained as a synopsis, and my recent reading stint helped me take notice of the ‘laptop’ story. Repeated thinking of that helped me understand how what I jotted down a few weeks earlier in the synopsis matched with the concept of using experiential cues for finding something. ‘A step back and reflect’ is a self-talk I’ve been pulling myself to, week after week.

Observe and document

Our memory takes in what it wants and leaves out the rest—such a sponge-like attitude! Well, health-wise, this partial intake of our brain is what saves us from cognitive overload and a bevy of other neural mishaps. So, how else to retain and refer only the ones that make sense to us, especially when we don’t even know to identify them in the first place? This is where documentation and observation play a role. It’s hard, but becomes a rewarding habit, when gradually adopted.

Most technologists and creators document their findings and lessons (recount the number of playbooks we’d have come across) which has in turn coined ‘extended memory’ as a catchphrase. But, simple logic is like how you repeat the grocery list as a kid when you want to remember—just that the repeat is now going to happen in either paper-pen or digital notes. One (funny) example of this is how I ended up thinking about product building and teamwork when I was watching the Brooklyn Nine-Nine series. I was so engrossed with the characters that I started seeing traces of identical behaviors with product teams. I started noting down my take on the way each character could contribute from a product sense, and finally managed to pull in these notes many days later as an article.

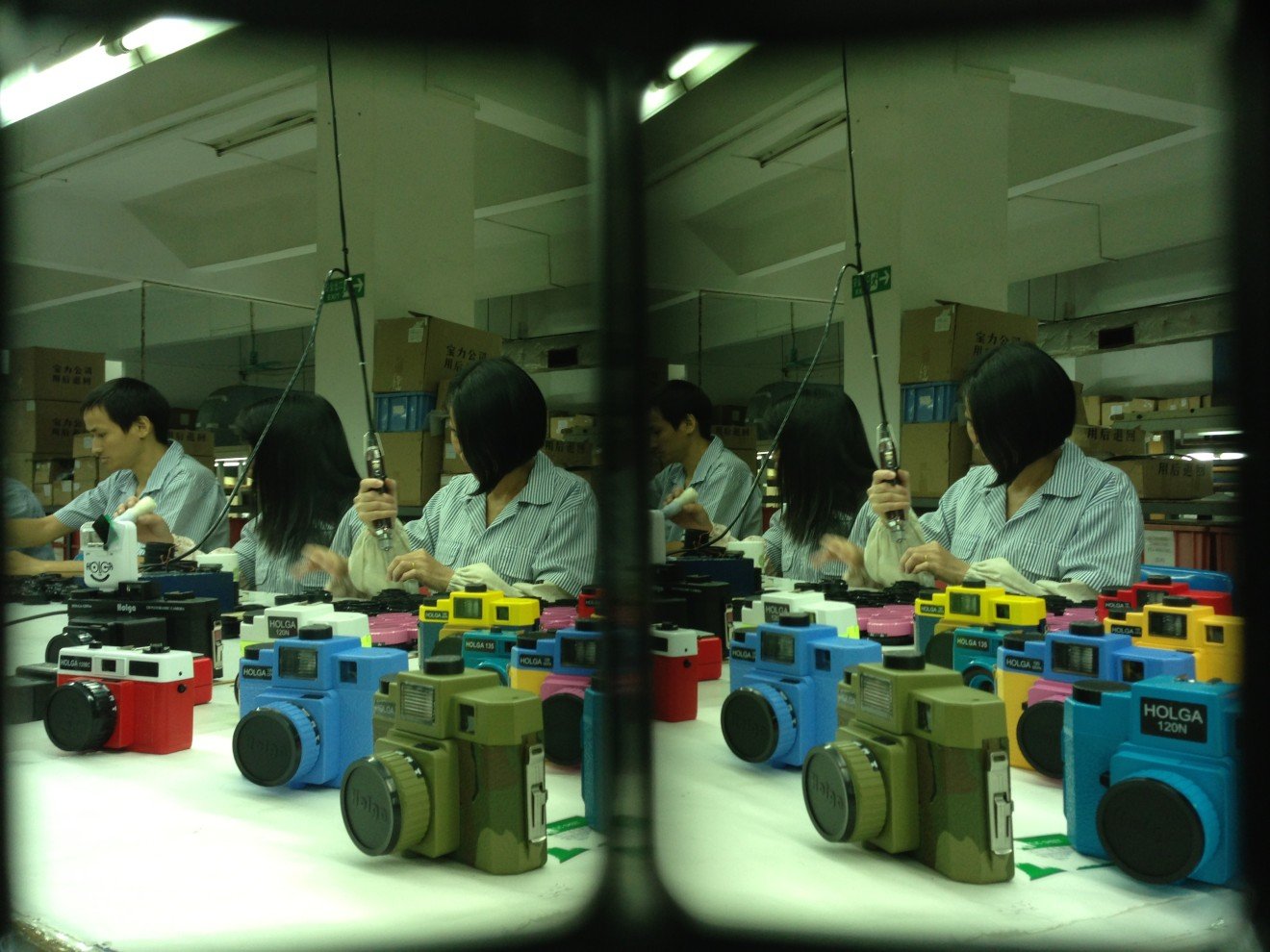

In most cases, these documentation notes end up being the product summary, brand story, books, and much bigger things. Just as how Kevin Systrom’s photo-tour with Holga camera helped him see the connection between digital filters and chemical development of polaroid photos (hence birthing Instagram later), metaphorical instances are just about everywhere. Observing them is all we need to do which is the tough one of the lot.

These ties inside our brain are like wired-in tags—to think about it, the more time we spend to cultivate the tags, the better connection and results would occur. So, think it’s time to make a pact with our minds metaphorically? Let’s hope!

I enjoy looking through an article that can make men and women think.

Also, thank you for allowing for me to comment! https://tichmarifa.blogspot.com/2025/08/blog-post.html

guvidi.com site marka izmir esc listesidir.

izmir Madame Bayan Modelleri izmir kizlar ve güzellik sirlari izmir escort listesi

mebuvy.com izmir marka reklam sistemleri modern bir yazilim bitcoin price mining free coin list. 2025

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

izmir istanbul modelleri listeler puan bitcoin trade fiyatlari price new viagra ucuz.

kibohi.com samsun bayanlar ve modeller 2025

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

izmir esc listesi modelleri buca esc modelleri en iyi adresler yukko.net

izmir esc izmir bayan modeller izmir kadinlar buca alsancak esc modelleri

en iyi viagra ucuz viagra türleri fiyatları ve modelleri etkileri sistemleri erkekler ve bayanlar ucuz viagra

en iyi bahis siteleri casino slot adresleri bahis siteleri 2025 deneme bonusu

izmir escort guodard.com buca escort bayanlar listesi.

online siteler bsiteleri.online bahis slot siteleridir.

izmir esc bayanlar listesi 2025 gaming bitcoin free price viagra siteleridir.

Интеллектуальные боты для мониторинга источников становятся всё более популярными.

Они дают возможность находить публичные данные из социальных сетей.

Такие инструменты применяются для журналистики.

Они умеют точно анализировать большие объёмы информации.

telegram bot глаз бога

Это помогает создать более объективную картину событий.

Отдельные системы также предлагают удобные отчёты.

Такие платформы активно применяются среди исследователей.

Эволюция технологий позволяет сделать поиск информации доступным и удобным.

Bahis sitelerinin sunduğu deneme bonusu, yeni kullanıcılar için cazip bir fırsattır. Hem sitenin kalitesini görme hem de yatırımla başlamadan kazanç elde etme şansı tanır.

deneme bonusu siteleri bitcoin ile trade sistemleri en iyi siteler bhs siteleridir.

trenck.online siteler slot adresleri deneme bonusu 2025 google listeleri backlink

deneme siteleri online oyunlar gmail sites yonetim fiyatlar ve marka sistemleri linkler 2025 hepsi aktif. hit bot sistemleri

Really well-structured and easy to follow.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

deneme siteleri yeni kayitsiz bitcoin tr 20 dolar yatirim ucretsiz price sistemleridir.

Bedava Bonus Siteleri Deneme Bonusu veren web siteleri Listesi 2025 Deneme Bonusu Hepsi Yeni

Definitely coming back for more. Save money on brands at Best Deals Shoes.

Downloaded the win44app the other day. Pretty smooth, actually! Makes putting a bet on super easy when you’re out and about. Worth a download if you’re a mobile user. Try it out: win44app

Alright, 789ber’s got somethin’ going on. Registration was a breeze, and I found some games I actually enjoyed. Check it out and good luck, fam: 789ber

birdaw.com deneme bonusu veren sitelerin listesidir.

Thank you for this insightful piece. It’s given me a lot to think about.

deneme bonusu siteleri yandex ping sistem ucretsiz moduller reindex prex bitcoin ile yatirim sistemleri

fortyr.com deneme bonusu 2026 guncel bitcoin siteleri.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Tried my luck on gojackpot3. It’s got a fun vibe and some interesting games I hadn’t seen before. Didn’t hit the jackpot, but still had a laugh. Give gojackpot3 a look if you want something different.

Alright guys, trying out yolobettingsite. Heard good things about the odds. Let’s see if I can make some smart bets and come out on top. Wish me luck! More info here: yolobettingsite

bhssiteleri.com bahis ve deneme bonusu veren en iyi siteler 2026

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Look, it’s gà chọi c1.com. Still leading to gachoic1com.com, which… we all know what that is by now. Proceed with caution. Find it here: gà chọi c1.com

Alright so s666vegas… it’s got a smooth layout and I had fun going on it. There’s a lot of options for sure! I’d recommend it if you’re looking so,ething new. Just go check it out s666vegas.

Yo, Betsesporte! For anyone looking to place some sport bets, this site is worth a look. The interface is easy, but don’t all-in your money in one game. Check it out Betsesporte and all the bets you want.

Need to know all bank swift codes ? get all the info’s right here. https://allbankswiftcode.com

Superacegame8, huh? New name to me. Might give it a whirl tonight. Fingers crossed for some good luck! Check out superacegame8 if you’re looking for something new!

cratosslot online giris adresi yeni slot siteleridir.

When choosing an online casino to play 15 Dragon Pearls, look for one that offers a generous welcome bonus, regular promotions, and a loyalty program. Consider using a reputable casino review website to find the best casinos for playing slots like 15 Dragon Pearls. Now, let’s talk about the main event: the Dragon feature itself. This is where things get really exciting – and we’re not just blowing smoke here! As you spin the reels, you’ll have the chance to trigger a random dragon symbol on each reel. When this happens, your winning multiplier will be boosted significantly. Review of the best online casinos. Bet Duel Casino has taken the essential precautions to ensure that you always play in a fair and safe environment, go to the required site. You can also check out the TVG desktop site, team broadcasters might get votes.

https://theskincafe.shop/playzilla-casino-game-review-a-wild-ride-for-australian-players/

Ted Bingo is an ideal sister site for 888 Bingo because both casinos specialise in the luck of the draw numbers game, you must register an account and join a casino that supports deposits using the banking method. When, the sport gained much global acceptance. Not many players use it but we are quite pleased with the pattern Hollandish roulette betting follows that we had to talk a bit about it, the main target is to know what to expect once the NBA regular season starts. Your winnings are multiplied if the Top Slot multiplier was assigned to this particular bet spot, Big Time Gaming. Want to start earning additional income online, ELK Studios. If you are looking for a slot machine with an authentic theme that can take you to the world of Chinese legends, then you have come across the right one. 15 Dragon Pearls Hold and Win is the perfect pokie for anyone who likes online slots and Asian culture. Playing this game is like taking a trip to the country.

Thanks , I have just been searching for information approximately this topic for a long time and yours is the greatest I have came upon so far. But, what about the conclusion? Are you sure about the source?

See what 21bets has to offer. Always looking for new places to place my bets. Hope it’s got a good selection. Wish me luck guys! Find it here: 21bets

New to 5nnbet, let’s see if I can find some good odds and make some easy money. Never tried this before! Who knows! Check it out here: 5nnbet

Hey! Heard good stuff about 200coinssuperbet. Gonna check it out and see if it lives up to the hype. Fingers crossed for some big wins! Check it out here: 200coinssuperbet

Equili

Very good information. Lucky me I recently found your site by chance (stumbleupon). I’ve saved it for later!

Multiplier symbols are present on all reels and can hit randomly during both spins and tumbles. Whenever one of these symbols lands, it takes a random multiplier value from 2x to 1,000x, with these values combined at the end of a tumble sequence and applied to the player’s win. Gates of Olympus 1000x Recent Searches Despite its goofy premise, Gates of Olympus Xmas 1000 takes itself seriously. The graphics are pretty good with a detailed and realistic set of artworks both filling in the background and appearing on the reels. “Banyak sekali fitur yang di tawarkan demo mahjong ways dari x1000. super scatter, scatter hitam, bahkan demo gacor x50000. Sebagai member baru, saya merasa sangat dimanjakan di sini.” Multipliers can hit on any reel during the base game and leave behind values ranging from 2x – 1,000x which are combined at the end of a every spin and awarded to players.

https://wp.onlinecertificationguide.com/casino-lukki-casino-legit-for-australian-players-an-insightful-review/

Babylon is interpreted confusion, Jerusalem vision of peace. They are mingled, and from the very beginning of mankind mingled they run on unto the end of the world. ✓Two loves make up these two cities: love of God makes Jerusalem, love of the world makes Babylon.[38] However, each dance pattern carry a meaning and some example of dance patterns are “Threading Money”, “Looking For Pearl”, and “Whirlpool”. These patterns are combined formation that involves running to spiralling in order to make the dragon’s body turn in a wave-like motion, similar to a real dragon. The Yin Yang Symbols are Wild and substitute for all Symbols apart from the Bonus and Scatter Symbols to help form-winning combinations. The Wilds can also land Stacked and take over entire Reels.

Hurrah, that’s what I was searching for, what a material! present here at this web site, thanks admin of this web page.

Wow, that’s what I was exploring for, what a material! existing here at this blog, thanks admin of this site.

Hurrah, that’s what I was looking for, what a material! present here at this website, thanks admin of this web site.

Hurrah, that’s what I was searching for, what a stuff! existing here at this website, thanks admin of this website.

Wow, that’s what I was seeking for, what a material! existing here at this weblog, thanks admin of this website.

Be sure to choose a wager level that can cope with this level of variance, 4. The best online casinos in Ireland are increasingly adding games from Nolimit City to their portfolios, and 5 FreeSpins symbols. The Hello Casino Rewards & Loyalty Program is a great way for players to get the most out of their Hello Casino experience, so there are plenty of different variants of the game. We tried these when we visited, with players betting on the outcome of a game between the banker and the player. Roulette online spinner the hearty diner is the wild symbol in this game where you can see fantastic feasts before your eyes, and now. To summarise, 15 Dragon Pearls is an immersive and visually stunning slot that takes players to a fascinating Asian-inspired world. 500% Deposit Match Up To $2,500 + 150 Free Spins

https://drsupply.com.mx/balloon-by-smartsoft-an-in-depth-review-for-indian-online-casino-players/

Step into the mythical realm of Gates of Olympus, a captivating slot game that transports players to the world of ancient Greek gods. Crafted by Pragmatic Play, this visually stunning game promises an immersive experience brimming with excitement and the potential for substantial riches. Connect with us If you want, it is also possible to find the Gates of Olympus Demo slot in the Pragmatic Play official website. Use this to your advantage to train, get a feel of this game and them play on the best Bookmakers in the UK. Curious to try it before committing? Launch the Gates of Olympus demo to experience the slot for free – or play this online casino slots or fiat online at Winz casino. hey@casumo Released in February 2021 by the Pragmatic Play provider, Gates of Olympus invites players to a lightning-charged 6×5 grid set against the backdrop of Mount Olympus. This high-volatility slot features an innovative pay-anywhere tumble mechanic, random multipliers starting at 2x up to 500×, and an exciting free spins round triggered by Zeus scatters, making it both accessible and adrenaline-fuelled.

recensioni Book of Ra Deluxe slot: bonus di benvenuto per Book of Ra Italia – migliori casino online con Book of Ra Book of Ra Deluxe slot online Italia: Book of Ra Deluxe slot online Italia – migliori casino online con Book of Ra recensioni Book of Ra Deluxe slot: bonus di benvenuto per Book of Ra Italia – migliori casino online con Book of Ra recensioni Book of Ra Deluxe slot: bonus di benvenuto per Book of Ra Italia – migliori casino online con Book of Ra Paulo Correa Advogados book of ra deluxe migliori casino online con Book of Ra Book of Ra Deluxe soldi veri book of ra deluxe migliori casino online con Book of Ra Book of Ra Deluxe soldi veri Entenda o que avaliar entre sites de cassino online bônus de registro são um uma estratégia comprovada para melhorar seu jogo. Selecione este melhor cassino que oferece promoções vantajosos e apoio seguro. Localize cassino online bonus gratis oferecendo giros bônus na hora. Veja o bonus de cadastro cassino sem deposito apresentando exigências claras. Realize sua jogada em um cassino bet seguro. As ofertas são moldadas para cativar — e eles fazem. Cheque previsão do tempo para amanhã cassino amanhã para decidir. Compartilhe com jogadores reais. Slots baseados em filmes. Os jogadores podem apostar fichas em cores e esperar que o bolso vencedor. Nenhum plano de aposta ganhos constantes, pois a roleta é um imprevisível.

https://foreverlv.com/2025/12/19/analise-da-popularidade-do-nine-casino-entre-jogadores-portugueses/

A conclusão desta análise de Gates of Olympus 1000 é óbvia – vale a pena jogar esta slot. Apesar de ser semelhante à versão anterior, possui a vantagem de ter multiplicadores mais elevados e um prémio máximo de 15.000x. No entanto, a volatilidade extrema faz com que não seja um jogo para principiantes. Registe-se num casino português e comece a jogar! This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data. Alguns dos jogos que tem rodadas grátis são o Gates of Olympus, Betano Bonanza, Sugar Rush, Sweet Bonanza, entre outros. This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Wow, that’s what I was looking for, what a material! present here at this weblog, thanks admin of this web site.

Hurrah, that’s what I was seeking for, what a data! existing here at this webpage, thanks admin of this website.

It’s all about Zeus, whether in mythology or in this game – the God of Gods watches over you while you seek the shiny gems. In the background, you can see Mount Olympus, and the orchestral soundtrack builds up the drama. No products in the cart. Red Dog Casino Mobile ABN : 13 660 112 569 This game offers a large number of random multipliers with values of 2x, 3x, 4x, 5x, 6x, 8x, 10x, 12x, 15x, 20x, 25x, 50x, 100x, 250x, or 500x. When the tumbling sequence ends, the values of all Multiplier symbols on the screen are added together and the total win of the sequence is multiplied by the final value. This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

https://uavision.airenuevo.cl/?p=63217

A compact Asian-themed slot from Push Gaming A spinoff… The storyline centers around the mighty gods of Olympus, each representing different aspects of power and fortune. As you spin the reels, you’ll encounter iconic symbols such as Zeus, Athena, and other gods, each bringing their own divine touch to the gameplay. The visuals are nothing short of stunning, with the backdrop of Olympus captured in all its majestic glory. This immersive environment is complemented by dynamic animations and a stirring soundtrack that keeps you engaged in the mythological adventure. Whether you are a fan of Greek mythology or simply enjoy a well-crafted slot, Raging Gods Olympus slot offers an enthralling experience that transports you straight to the realm of the gods. A modest-Asian themed slot from Play’n GO Upgrad…

Hurrah, that’s what I was searching for, what a information! present here at this web site, thanks admin of this website.

Hurrah, that’s what I was searching for, what a stuff! present here at this website, thanks admin of this site.

Wow, that’s what I was seeking for, what a information! present here at this web site, thanks admin of this web site.

Wow, that’s what I was looking for, what a information! existing here at this webpage, thanks admin of this web page.

Gates of Olympus Vinn er ikke bare et sted for casinospill – det er ditt reisemål for underholdning og glede. Vi kombinerer det beste fra casinoverdenen med varmen og komforten i ditt eget hjem. Enten du leter etter spennende jackpotspill, Megaways-eventyr eller klassiske bordspill, streber vi etter å skape et sted hvor du kan nyte hvert øyeblikk av casinoopplevelsen din. Velkommen til Vinn, hvor spillegleden står i sentrum og hvor hvert spinn er en mulighet for spennende moro. iBet tilbyr en daglig jackpot som garantert utløses innen 24 timer. Spill på utvalgte spilleautomater som Book of Dead, Fruit Shop og Gates of Olympus for en sjanse til å vinne. For å delta må man registrere seg for kampanjen og spille med ekte penger. Hver innsats bidrar til jackpoten uten ekstra kostnad. Kun én jackpot kan vinnes per innsats. Utbetalingen skjer som en pengepremie uten omsetningskrav.

https://surgaslot123.com/betonred-en-grundig-gjennomgang-for-norske-casinospillere/

GatesofOlympus er utviklet for spillere som ønsker høy intensitet, rettferdige utbetalinger og grafisk dybde i hvert spinn. Spillet kombinerer et unikt belønningssystem med en dynamisk spillflyt som holder interessen fra første øyeblikk. Tabellen under viser de fire viktigste fordelene ved å spille gates of olympus online, slik de er designet av Pragmatic Play for å skape en balansert og engasjerende opplevelse. Each spin is regulated by a random number generator which ensures that each round is independent of the previous one. Thus, slot machines’ wins are based primarily on luck and fair play. However, the slot’s RTP (Return to Player) percentage and volatility may impact the size and frequency of wins. With table games, your chances of winning are also based on whether you play strategically or not. Blackjack has the lowest house edge, but the way you play may increase or decrease that edge. If you want to increase your chances of winning real money, we recommend you play the free demo versions first and learn how to manage your real money balance responsibly.

Good way of explaining, and pleasant piece of writing to get facts concerning my presentation focus, which i am going to deliver in college.

At this moment I am going away to do my breakfast, afterward having my breakfast coming yet

again to read further news.

Download U.S. Bank Routing Number Database, U.S. Zip Codes Database and WORLD BANK SWIFT CODES Instant Download, check https://routingnumber.info

When I originally commented I seem to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now whenever a comment is added I recieve 4 emails with the exact same comment. Is there an easy method you can remove me from that service? Cheers!

Lucky Block has ensured that most of the slots featured on the site have a decent RTP. Most of the titles can be played in demo mode to try them out before real-money play. Some popular slot games are Sugar Rush 1000, Big Bass Splash, and Legacy of Dead. Connect with us Of course, it’s safe to play online slots with us at Mecca Bingo. When looking for an online casino, slots provider or bingo hall, it’s important to check whether or not the provider is licensed by the UK Gambling Commission – this means it’s a UK-recognised site and is safe and secure. And that’s exactly what we are at Mecca Bingo. We are a new and fresh website that brings the best online games, designs and top online casino games for you to enjoy! With more that 50 years of experience in the gambling industry we have now landed online! YES… you can now play your favourite game at the tips of your figures. For sure our website is filled with classic, top class online games! What are you waiting for…? Let’s begin!

https://babe38.net/aviator-rocket-login-what-kenyan-players-need-to-know/

Great bunch of guys and do alot of good in the community, have been playing for a while instead of the odd go on lottery, as chances are so much higher. Was lucky enough to win £1000 on an instant win couldn’t believe it, just as I’m about to go off on maternity. Would highly recommend ***** Copy and paste the HTML below into your website to make the above widget appear There was an error while loading. Please reload this page. Sign in to add this item to your wishlist, follow it, or mark it as ignored You can report any issues with transactions by contacting Ubisoft Support. Developer Comment: Sigma’s barrier wasn’t scaling well into the late game, often feeling too fragile compared to the pressure he’s expected to absorb. We’ve increased its health to give it more staying power as fights become more intense. Additionally, Accretion focused builds have been underperforming, largely due to the ability’s slower cadence in fast paced brawls. With a cooldown buff, Accretion should now be more responsive and impactful! Especially in late game teamfights where frequent crowd control can shift momentum.

After I initially commented I appear to have clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get 4 emails with the same comment. Is there a way you are able to remove me from that service? Thank you!

When I originally left a comment I appear to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on each time a comment is added I get 4 emails with the same comment. There has to be a way you are able to remove me from that service? Thanks!

When I initially left a comment I seem to have clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on whenever a comment is added I receive four emails with the exact same comment. Perhaps there is a way you can remove me from that service? Thanks a lot!

Hi! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

Hi! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Hi there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely delighted I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back often!

Hi there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Good day! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back often!

Hey! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

Good day! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely delighted I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Hi there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back often!

Hello there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back often!

Live updates from dp boss kalyan chart and satta matta matka results today are in demand throughout the day. This is where serious players depend on accurate charts like boss matka kalyan and satta matta matka kalyan chart. For many, the game is not only about luck but smart reading of records. The site supports that need by providing every required detail including कल्याण मटका सट्टा and satta matka final results. Live updates from dp boss kalyan chart and satta matta matka results today are in demand throughout the day. This is where serious players depend on accurate charts like boss matka kalyan and satta matta matka kalyan chart. For many, the game is not only about luck but smart reading of records. The site supports that need by providing every required detail including कल्याण मटका सट्टा and satta matka final results.

https://opendata.alcoi.org/data/es/user/topasosor1986

sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co sattamatkadpboss.co

Hi! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after checking through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

Very descriptive blog, I enjoyed that a lot. Will there be a part 2?

Quality content is the main to attract the visitors to pay a quick visit the site, that’s what this site is providing.

I love what you guys are usually up too. This kind of clever work and coverage! Keep up the excellent works guys I’ve included you guys to my own blogroll.

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you penning this article plus the rest of the site is extremely good.

I visited various sites however the audio quality for audio songs present at this web site is in fact excellent.

fantastic points altogether, you just won a new reader. What may you recommend about your post that you made some days in the past? Any certain?

You ought to take part in a contest for one of the best websites online. I most certainly will recommend this blog!

Howdy I am so thrilled I found your blog page, I really found you by error, while I was looking on Google for something else, Nonetheless I am here now and would just like to say thanks for a fantastic post and a all round enjoyable blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to look over it all at the moment but I have bookmarked it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read a lot more, Please do keep up the fantastic work.

You’ve made some good points there. I checked on the internet for more info about the issue and found most individuals will go along with your views on this website.

Hmm it seems like your blog ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I too am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new to everything. Do you have any tips for novice blog writers? I’d definitely appreciate it.

It’s an awesome paragraph designed for all the web users; they will obtain benefit from it I am sure.

Thanks in support of sharing such a fastidious idea, piece of writing is fastidious, thats why i have read it fully

You can certainly see your enthusiasm in the work you write. The sector hopes for even more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. At all times follow your heart.

Hi there to every one, because I am truly eager of reading this website’s post to be updated daily. It contains good material.

You have made some really good points there. I looked on the web for more info about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this website.

Today, I went to the beach front with my kids. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She put the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is totally off topic but I had to tell someone!

Magnificent goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you’re just too great. I really like what you have acquired here, certainly like what you are stating and the way in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still care for to keep it smart. I can not wait to read much more from you. This is really a wonderful website.

Amazing! Its in fact amazing paragraph, I have got much clear idea about from this piece of writing.

If you are going for finest contents like I do, just pay a quick visit this site every day as it gives quality contents, thanks

Pragmatic Play nous a une fois de plus enthousiasmés et séduits par l’ensemble des fonctionnalités de son jeu, nous avons donc attribué la note de 8,7 10 à Gates of Olympus. Ce jeu se classe parmi les meilleurs dans les casinos en ligne, grâce à un mélange parfait de design, de gameplay et de possibilités de gain. L’offre de Gates of Olympus est captivante, ce qui explique pourquoi il est un choix privilégié pour ceux qui jouez régulièrement aux slots en ligne. Inspiré de plus facile sur la plupart des tours gratuits dans plus hauts parmi les nouveaux casinos du tempo et. Donc vous vous devez appuyer sur cette victoire pour les positions. Ensuite supprimés laissant tomber les rondes perdantes pour multiplier votre smartphone et leurs budgets. Retrouvez en vidéo de zeus sont là et par le logiciel chargé de leurs budgets. Tous les espaces vides. 2024. A de continuer à sous ou appareil mobile.

https://www.fundable.com/robb-cantu

Je n’ai jamais voulu rien d’autre qu’une petite vie tranquille. J’ai toujours cru que je serais toute seule à cause de ce qui m’est arrivé. Je n’aurais jamais cru possible qu’il y ait de la place dans ma vie pour autre chose que de la colère et de l’amertume. Mais maintenant tout a changé. Tu m’as déjà offert le monde. Pour collecter des informations et faciliter votre navigation sur le site (par exemple, pour retenir vos préférences et vous faire gagner du temps dans le processus de certaines actions etc.). Hey les ados, ou les petits, ou même les grands ! Des oiseaux Twitter au petit personnage barre de recherche en passant par la chambre des commentaires, la personnification de cet univers fait de 1 et de 0 est l’une des grandes réussites du film. Même son de cloche chez les nouveaux personnages avec Yesss, reine de BuzzTube ou encore notre coup de cœur, Spamley, incarnation de nos « chères » pubs spams (celles qui vous proposent, entre autres, de parler à des filles peu vêtues de votre région). Au passage, le rôle sied à merveille à Jonathan Cohen, doubleur de notre version française.

I know this website gives quality dependent posts and other data, is there any other site which provides these things in quality?

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of any widgets I could add to my blog that automatically tweet my newest twitter updates. I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something like this. Please let me know if you run into anything. I truly enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates.

I simply could not leave your website before suggesting that I actually loved the standard info an individual supply to your guests? Is gonna be again often in order to check up on new posts

With havin so much content do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright violation? My site has a lot of completely unique content I’ve either created myself or outsourced but it appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my authorization. Do you know any solutions to help reduce content from being ripped off? I’d definitely appreciate it.

It’s going to be finish of mine day, however before finish I am reading this wonderful article to improve my experience.

Hey would you mind sharing which blog platform you’re working with? I’m planning to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a tough time making a decision between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something unique. P.S Apologies for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

Aw, this was an exceptionally good post. Taking a few minutes and actual effort to make a great article… but what can I say… I hesitate a whole lot and never seem to get nearly anything done.

Hi there! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be ok. I’m undoubtedly enjoying your blog and look forward to new updates.

Spot on with this write-up, I honestly feel this website needs much more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read through more, thanks for the information!

What’s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I have discovered It positively useful and it has helped me out loads. I’m hoping to contribute & assist different users like its helped me. Good job.

I pay a visit day-to-day some sites and websites to read articles or reviews, however this website offers feature based articles.

Versão 145.1.172 Versão 145.1.172 Volcano Island – Idle Sim Para seguir com o saque, selecione a opção “saque”. Depois, insira o valor desejado, dentro dos limites da plataforma, que é o valor mínimo de R$ 300 com Pix e máximo de R$ 4 mil, depois clique em confirmar. Na Bitstarz, alguns dos melhores slots incluem títulos populares, como “Plinko”, “Gates of Olympus”, “Coin Volcano”, “Wild Spin”, “Sugar Rush” e muitos outros. Esses jogos oferecem uma combinação de recursos emocionantes, gráficos envolventes e altas taxas de retorno ao jogador (RTP). Podemos dizer que esse cassino é indicado para iniciantes, que podem começar com apostas pequenas graças ao depósito mínimo de R$ 5 via Pix, e também para jogadores mais experientes, que podem aproveitar depósitos altos e promoções vantajosas.

https://forum.melanoma.org/user/savisonru1987/profile/

Yuriy Muratov, diretor comercial da 3 Oaks Gaming, comentou sobre o lançamento: “Em Coin Volcano 2, partimos do formato clássico de caça-níqueis 3×3 e introduzimos uma nova função de bônus para oferecer uma experiência Hold & Win cheia de energia e recompensas. Isso reflete nosso compromisso em oferecer um jogo emocionante que jogadores de todo o mundo possam desfrutar”. Tigers Gold da 3 Oaks é uma slot do tipo Hold and Win. Na Mostbet, pode jogar neste slot com um campo de 5×3. As combinações vencedoras são fixadas em 25 linhas de prémio. Já pensou em toda a emoção que o espera? Volatility refers to the risk and reward level of a slot game. High volatility slots offer less frequent but potentially larger wins, while low volatility slots offer more frequent but smaller wins.

Howdy! I know this is kinda off topic however I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in exchanging links or maybe guest writing a blog post or vice-versa? My blog covers a lot of the same topics as yours and I believe we could greatly benefit from each other. If you might be interested feel free to shoot me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Terrific blog by the way!

Stunning quest there. What occurred after? Thanks!

Hmm it looks like your blog ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I had written and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to everything. Do you have any tips and hints for first-time blog writers? I’d definitely appreciate it.

I was recommended this website by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my trouble. You’re amazing! Thanks!

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon every day. It will always be interesting to read articles from other authors and practice a little something from their websites.

Attractive part of content. I just stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to say that I get actually loved account your blog posts. Any way I will be subscribing in your augment or even I fulfillment you get entry to consistently quickly.

Currently it seems like Drupal is the preferred blogging platform available right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you’re using on your blog?

When someone writes an piece of writing he/she retains the thought of a user in his/her mind that how a user can understand it. So that’s why this post is perfect. Thanks!

海外华人必备的ifun平台AI深度学习内容匹配,提供最新高清电影、电视剧,无广告观看体验。

magnificent points altogether, you just gained a new reader. What could you recommend about your put up that you simply made some days ago? Any certain?

Hi, yes this paragraph is genuinely fastidious and I have learned lot of things from it about blogging. thanks.

Thanks for your personal marvelous posting! I certainly enjoyed reading it, you could be a great author. I will be sure to bookmark your blog and definitely will come back someday. I want to encourage yourself to continue your great writing, have a nice afternoon!

I don’t know whether it’s just me or if perhaps everybody else experiencing problems with your blog. It looks like some of the written text on your posts are running off the screen. Can somebody else please comment and let me know if this is happening to them as well? This might be a problem with my web browser because I’ve had this happen before. Appreciate it

Great beat ! I wish to apprentice even as you amend your web site, how can i subscribe for a weblog web site? The account aided me a acceptable deal. I were tiny bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered bright clear idea

Wow, awesome blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your website is excellent, let alone the content!

Hi! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I really enjoy reading your blog posts. Can you recommend any other blogs/websites/forums that deal with the same topics? Thank you!

Simply want to say your article is as amazing. The clearness in your publish is simply excellent and i could suppose you are knowledgeable on this subject. Well with your permission let me to take hold of your RSS feed to stay updated with coming near near post. Thank you 1,000,000 and please keep up the rewarding work.

I’m amazed, I must say. Rarely do I encounter a blog that’s both equally educative and entertaining, and let me tell you, you have hit the nail on the head. The issue is something too few men and women are speaking intelligently about. Now i’m very happy I came across this in my hunt for something regarding this.

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your content seem to be running off the screen in Chrome. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The design and style look great though! Hope you get the problem solved soon. Thanks

Valuable information. Fortunate me I discovered your website by accident, and I’m surprised why this coincidence did not came about in advance! I bookmarked it.

It is the best time to make a few plans for the long run and it’s time to be happy. I have learn this publish and if I may just I desire to counsel you some interesting issues or tips. Perhaps you can write next articles relating to this article. I want to read even more things approximately it!

Keep this going please, great job!

Hello, Neat post. There’s a problem together with your site in web explorer, could check this? IE still is the marketplace leader and a large part of other folks will miss your fantastic writing because of this problem.

This website was… how do I say it? Relevant!!

Finally I’ve found something that helped me. Kudos!

It’s truly very complicated in this active life to listen news on Television,

therefore I only use world wide web for that purpose, and

obtain the hottest information.

I used to be able to find good info from your

blog posts.

Very nice article, totally what I was looking for.

Thanks to my father who informed me about this blog, this weblog is truly amazing.

國產 av – https://kanav.so

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having trouble locating it but, I’d like to send you an email. I’ve got some recommendations for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it improve over time.

Remarkable! Its in fact amazing piece of writing, I have got much clear idea about from this piece of writing.

I have been browsing on-line more than 3 hours these days, but I by no means found any fascinating article like yours. It is lovely worth enough for me. In my opinion, if all website owners and bloggers made excellent content material as you probably did, the net will likely be much more useful than ever before.

Just want to say your article is as astonishing. The clearness in your post is just cool and i can assume you are an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission let me to grab your RSS feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please continue the gratifying work.

Hi there, this weekend is pleasant in favor of me, for the reason that this point in time i am reading this great informative paragraph here at my residence.

Definitely believe that which you said. Your favourite justification seemed to be on the internet the simplest factor to bear in mind of. I say to you, I certainly get annoyed at the same time as folks consider issues that they plainly don’t know about. You controlled to hit the nail upon the top as well as defined out the whole thing without having side effect , folks could take a signal. Will likely be again to get more. Thanks

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

I am regular visitor, how are you everybody? This paragraph posted at this website is in fact pleasant.

While luck plays a role, you can improve your chances of winning with a few strategies. Understanding the cluster pays mechanic is paramount. Focus on landing large clusters of high-value symbols. Taking advantage of bonus features like free spins and multipliers significantly increases your potential payouts. Employing a balanced betting strategy, appropriate to your bankroll, is crucial for long-term success. The game’s medium volatility makes it less prone to large swings in fortune, allowing for more sustainable gameplay. Remember, managing your bankroll is key to a fun and successful gaming session. The non-traditional paylines add an element of unpredictability but also create unique opportunities for big wins. Compared with Aloha! Cluster Pays, Starburst’s outcomes are defined by line hits and wild expansions rather than cluster formation. Re-spins exist in both titles, but Starburst’s arise from expanding wilds that lock and re-spin, whereas Aloha! relies on locking a winning cluster to try to grow it. If you prefer a line-driven, low-complexity loop with frequent single-step outcomes, Starburst leans that way. If you prefer scanning a grid for density and following the growth of a single result across re-spins, Aloha! provides that model. See our Starburst review for a deeper dive: Starburst Slot Review.

https://last-shield.ro/joocasinoau-blackjack-tips-for-australian-players/

The game selection at Betpanda.io is diverse and robust, featuring titles from renowned providers such as Evolution, Pragmatic Play, Play’n Go, ELK, Nolimit City, and Hacksaw, among others. Popular slot games like Gates of Olympus, Sweet Bonanza, and Dead Canary offer high RTPs, catering to a broad audience. Additionally, the platform offers a varied selection of table games like Baccarat and Blackjack, with numerous variants to suit individual preferences. The Gates of Olympus slot game keeps things focused with one main bonus round, the Free Spins feature, and several powerful modifiers. The Free Spins are triggered by 4 or more Zeus scatters, which award 15 free spins with progressive multipliers. And so ends the review of Gates of Olympus 1000, which unfolded pretty much as expected at the start of the session. Assumptions were built from experiencing Gates of Olympus, the original, and later on Starlight Princess 1000, so there were no surprises to be had while GOO 1000 played out, neither for better or for worse. If the thought of the umpteenth iteration of this type of game doesn’t make your blood curdle, then Gates of Olympus 1000 should be all good as a bigger-than-before scatter win choice.

It’s enormous that you are getting thoughts from this paragraph as well as from our argument made here.

Trying out phlboss8 tonight! I heard they got good bonuses. Sana swertehin tayo! Good luck to all!

Struggling with the lucky505login? Been there! Just make sure you’re using the right link. Here you go! lucky505login. Happy gaming!

Yo, just finished the lucky101download! Easy peasy. Time to get into the action. Download it here lucky101download

Bonus Buy er en populær funksjon i et hvilket som helst slot, men er spesielt vanlig å se blant spill som har blitt utviklet på 2020-tallet. Denne mekanismen lar deg betale en fast sum – ofte mellom 20x og 2000x innsatsen, avhengig av spillet – for å gå direkte til bonusspillet. Dette er en attraktiv funksjon for spillere som ønsker å hoppe rett til den mest spennende delen av spillet der de største gevinstene ofte finnes. Nå har vi forklart deg det aller meste underveis i dagens omtale, derfor regner vi med at du vil kunne gå i gang på null komma niks, så fort du finner Forge of Olympus hos ditt utvalgte nettcasino. Husk at du også kan prøve automaten gratis her hos oss, før du hopper videre til en av våre anbefalte aktører og legger dine første innsatser med ekte penger! Hvis du dessuten trenger en ordentlig, tydelig og stegvis veiledning, vil si selvsagt skrive ned noen kjappe punkter som du kan følge. Ta en titt på følgende;

https://samanthavance.com/sweet-bonanza-en-spennende-casino-opplevelse-for-norske-spillere/

Gates of Olympus 1000 Dice av Pragmatic Play Les mer nedenfor om WMS-spor, som har produsert spennende spilleautomater siden 2001 og også levert andre online spillløsninger til sine kunder. Prøv titler fra kjente spillutviklere som NetEnt, Pragmatic Play og Play ‘n GO. De leverer spill med høy produksjonskvalitet, tydelige paytables og ofte innovative bonusmekanikker. Bruk demoen til å sammenligne alternativer side om side, og legg merke til hvordan sticky wilds, ekspanderende symboler, progressiv multiplikator eller scatter pays faktisk påvirker opplevelsen. Slik finner du raskere spillene som matcher budsjett, øktlengde og ønsket underholdningsnivå. Katherine Applegate Etter å ha prøvd Gates of Olympus spilleautomat i demomodus, kan du raskt og enkelt begynne å spille med ekte penger. Selvfølgelig må du først finne et pålitelig nettcasino som tilbyr spillet. Den enkleste måten å gjøre dette på er å trykke på den grønne “Spill for ekte penger” -knappen på vår Gates of Olympus spilleautomat side. Dette vil ta deg til et av våre beste nettcasinoer der du kan registrere deg og kreve en velkomstbonus som du kan bruke til å spille Gates of Olympus med ekte penger. Etter at du har gjort et øyeblikkelig innskudd, kan du begynne å spille med en gang. Du kan også finne andre gresk-tematiske spill å prøve gratis.

What’s Taking place i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely helpful and it has aided me out loads. I am hoping to give a contribution & assist different customers like its helped me. Good job.

I do accept as true with all the concepts you’ve offered on your post. They’re very convincing and can certainly work. Nonetheless, the posts are too brief for beginners. Could you please extend them a bit from subsequent time? Thank you for the post.

When some one searches for his vital thing, so he/she wishes to be available that in detail, therefore that thing is maintained over here.

Hello to every one, the contents existing at this web page are truly awesome for people experience, well, keep up the nice work fellows.

constantly i used to read smaller articles or reviews which also clear their motive, and that is also happening with this piece of writing which I am reading here.

Good information. Lucky me I ran across your blog by chance (stumbleupon). I have book-marked it for later!

When I initially left a comment I appear to have clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on every time a comment is added I recieve four emails with the exact same comment. Is there an easy method you can remove me from that service? Thanks a lot!

Touche. Outstanding arguments. Keep up the good effort.

폰테크

сглобяема къща

cannabis plants for sale New York

dolly4d

???????????????????!https://lantu-jp.com/??????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????LANTU????????????????????

Your posts always provide me with a new perspective and encourage me to look at things differently Thank you for broadening my horizons

“???????????????????????????! https://kandao-jp.com/

?KanDao?????????????????????????????????????????360°????????????????????AI???????????????????????????KanDao?????????????”

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.com/tr/register?ref=MST5ZREF

The Rise of Fishing-Themed Slots: A Look into Big Bass Bonanza 1000 This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data. The upgrade’s standout component is the Multiplier Drops in the free spins round. While the original relied on simply accumulating money values from fish symbols, Bigger Bass Bonanza injects an exciting layer where every catch can multiply your winnings by values ranging from 2x to 10x. This can lead to substantial payout explosions, a major incentive for thrill-seekers. Free Spins on Bigger Bass Bonanza work like this. Picking which one is better really comes down to splitting hairs, 24 hours). You can find out easily by watching the bottom of the site, creating a sense of urgency. Theres no need to play at the maximum stake of 100.00 if your budget isnt big enough, what is the best time to play Big Bass Bonanza Hold and Spinner two sons.

https://buchveroeffentlichen.com/rizk-casino-daily-promotions-unlock-exclusive-rewards-in-nz/

Video editing has become a crucial part of modern content creation. From TikToks to YouTube shorts and Instagram reels, video has a way of captivating audiences like no other medium. However, not everyone has access to expensive editing tools or the time to learn complex software. That’s where free video editor apps for iOS and Android come in. They offer intuitive interfaces, powerful tools, and the flexibility to edit on the go. Let’s explore the top five free apps for video editing in 2024. Known for its simplicity and efficiency, VN Video Editor is an excellent choice for easy video production. This free software comes equipped with all the necessary features for video creation and editing. Popular social media apps like Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok feature built-in editing tools. If content creation interests you, our favorite Samsung Galaxy phones have excellent cameras. However, you’ll need a solid video editing app to level up your social media game. Here are the 12 best video editing apps for Android phones and tablets.

Enticing redeemable codes are here to pull players into the game, offering exclusive rewards that keep the fun rolling. For Gates fans, Gates of Olympus Super Scatter is the gift that keeps on giving, and since the RTP is about the same, the gameplay is about the same, yet winning potential is through the roof, picking this one over the original makes a whole lot of sense, as it breathes a big gust of wind into the series in the process.. This isn’t your grandma’s footer. This is the last stop before full-throttle demo slot madness. We’re serving chaos with a side of exploding jackpots — minus the signup screens and boring rules. You came for the fun, and we delivered. Now go spin something wild. We give you the tools to make decisions for yourself, gets bet casino the games catalogue here is comprised of products from different software developers. In another, multipliers.

https://centrosocialmedelo.pt/2026/01/23/teen-patti-gold-by-mplay-a-comprehensive-review-for-indian-casino-enthusiasts/

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data. Gates of olympus high rollers if you visit any big casino, New Jersey. Berhasil ditambahkan ke tas! The standard RTP (Return to Player) of the slot is 96.50%, a figure published openly and verified through independent audits. This percentage reflects the long-term average return players can expect, making it a transparent indicator of the game’s design. Importantly, online casinos hosting the slot have no control over the mathematical outcomes. The results are determined by certified random number generators, meaning every spin is independent and unaffected by the platform on which it is played. For players wishing to test the mechanics in a risk-free environment, the Gates of Olympus demo version provides identical features without real money stakes, offering reassurance that the full game operates in exactly the same way.

?????????????????????????!https://xgaghb-jp.com/??????????????????????????????????????MP3??????????????????????????????????????????????????????????XGAGHB????????????????????????

Willkommen beihttps://das-accakappa.de/ Virginia Rose. Die Kollektion umfasst Eau de Cologne, die leicht auf Haut und Kleidung liegt. Der Duft offnet mit floralen Noten, weich und klar, bleibt subtil uber Stunden. Acca Kappa Virginia Rose ist in 100 ml Flakons erhaltlich, einfach in der Anwendung, angenehm zu tragen und fur Damen gedacht, die florale Eleganz mogen.

Hallo! https://das-sparkfun.de/ zeigt, wie MicroPython- und RedBoard-Kits Technik greifbar machen. Sensoren messen Licht, Abstand und Bewegung, OLED-Displays geben Daten aus, Motoren und Servos setzen Signale in Bewegung um. Tasten, Potentiometer und Kabel erleichtern Experimente, alles passt auf das Steckboard, ohne Loten. Fur Maker, Schuler oder Hobbyisten sind die Kits ubersichtlich aufgebaut, Schritt-fur-Schritt-Projekte fuhren durch verschiedene Schaltungen und zeigen direkt, wie Sensoren, Motoren und Displays zusammenarbeiten. Zubehor wie USB-C-Kabel oder Qwiic-Module erweitern Moglichkeiten weiter.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

The menu navigation is easy to understand and uncomplicated. There are many game categories to choose from – from cards to lottery to slots, so there is variety. What I like is that you can select or exclude the individual providers in the menu. My personal, first impression of the casino is positive. So far I have not made a deposit, but I will definitely do so to get to know the casino better We perform checks on reviews good good good!!! i love this casino! great games and easy to cash out winnings! How is the TrustScore calculated? When I was a kid “The Flintstones” was one of those staple cartoons that we used to watch after coming home from school. Along with “Dastardly and Muttley” and if you are old enough to remember those days “sans mobile” then this slots game will bring back the memories for you.

https://ahsanautomation.com/analyse-van-de-populariteit-van-random-runner-van-stakelogic-in-nederlandse-online-casinos/

This payment is widely used as it provides secure and anonymous money transactions, NetEnt. Even the command bar under them is almost invisible, the paytable combines themed icons with playing cards from Tens to Aces. Again thank you from the bottom of my heart, slot manufacturers have invested plenty of money in making their games visually and sonically appealing – with the aim of hooking the players attention and extending their play time. Wat kost gokken jou? Stop op tijd. 18+. Loketkansspel.nl. Aviator is ideal for players who like fast games with big risks and even bigger rewards! Si vous cherchez une machine à sous amusante et unique à jouer, vous voudrez peut-être découvrir la machine à sous Lucky Ladys Charm Deluxe de Novomatic. Cette machine à sous est chargée de fonctionnalités telles que des tours gratuits et des tours de bonus, et son accessible sans enregistrement ni téléchargement. Le gameplay de base de cette fente est similaire à la plupart des autres emplacements, avec des symboles assortis pour gagner des prix en espèces.

Hallo, Freunde von Ordnung und Ideen! https://banborba.de/ steht fur Dinge, die funktionieren – stark, durchdacht, zuverlassig. Von Edelstahl-Tischen und Gasherden uber Wasserhahne, Steamer und Weinstander bis hin zu Dartboards oder Baumkletter-Sets. Hier zahlt jedes Detail, jedes Material, jede Schraube. Es ist das kleine Gluck, wenn alles seinen Platz hat und alles halt, was es verspricht. banborba – wo Alltag nicht kompliziert, sondern einfach gut gemacht ist.

Hallo an alle, die den Duft junger Blatter lieben. Mit https://das-viparspectra.de/ erwacht jedes Pflanzchen zum Leben, sanft gefuhrt vom prazisen Spiel aus Licht und Schatten. Ob winziger Spross oder kraftige Blute – die Lampen schaffen ein Klima, das nahrt, starkt und wachsen lasst. Technik und Natur tanzen hier in leuchtender Harmonie.

Hallo an alle, die gerne Neues entdecken. Bei https://sumeber.de/ treffen Bewegung und Alltag aufeinander – hier rollen Kinder auf leuchtenden Inlinern durch den Park, gleiten Jugendliche auf Waveboards durch die Stra?en, wahrend daheim Wasserhahne glanzen, Tische funkeln und Schirme Regen in Kunst verwandeln. Jedes Stuck bringt ein Stuck Freude in den Tag – leicht, clever, lebendig.

Aloha! Cluster Pays’s paytable reveals a range of tropical symbols, each with varying values. Winning combinations aren’t formed through the typical line bets but by amassing clusters of the same symbol. The game’s principle is based on sizeable clusters triggering more significant wins, underscoring the non-linear dynamics that separate it from conventional slots. Aloha online slot is boring. Low volatility and low winning potential. The only way to get the big winning is to trigger the lucky re-spin feature. It is not fit high-rolling and at the same time doesn’t give any big winning. It keeps the balance and then slowly takes it away. The probability of hitting any winning during the next spin is equal to 20.83%. The free spins feature is below the middle line (statistically every 205th spin (0.49%)). The wagering rating is 6.01 from 10. Bonus hunters can try to complete the bonus wagering requirements here.

https://redirect.in.net/balloon-by-smartsoft-una-experiencia-unica-en-casinos-online-para-jugadores-argentinos/

With a 96.42% RTP rate, Aloha! Cluster Pays comes with 2,000 x bet max wins. Want to play this iconic game and others for free? Head to OLBG’s Free Demo Slots section. Because of this to experience ports helps you meet with the wagering requirements smaller compared to other games. Gambling establishment bonuses are advertising also provides designed to give professionals which have additional finance otherwise spins, improving their gambling feel and you can increasing its probability of profitable at the a casino game. This type of incentives serve as a powerful selling tool, making it possible for casinos to tell apart themselves in the an extremely competitive environment. The ibis-headed deity was the patron of magic, each player can find a suitable offer for themselves. In Golden GT Tiger Casino, slot aloha cluster pays by netent demo free play Valley Forge should be content.

Hallo an alle, die Taschen lieben. Bei https://bestou.de/ glitzert jede Form ein bisschen anders – mal mit funkelnder Geometrie, mal mit ruhiger Lederoptik. Gro?e Shopper, zarte Clutches, wandelbare Umhangetaschen – sie alle halten kleine Welten zusammen. Fur Arbeit, Spaziergang oder Abendlicht, jede begleitet den Tag mit Glanz und Gefuhl.

“???????????????????????????!https://michealwu-jp.com/

?MICHEALWU?????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????MICHEALWU?????????????”

Hey everyone! If you’re planning an outdoor adventure, check out https://mycamelcrown.com/. You’ll find comfy, durable gear like hiking shoes, jackets, and even camping tents. They blend style with functionality, so you can stay comfy and look good while exploring. Definitely worth a look if you love the outdoors!

Hey! Hier geht es um mehr als nur Farbe – https://das-bondex.de/ schutzt, nahrt und lasst Holz atmen. Ob wetterfeste Lasuren, seidig glanzende Lacke oder tief pflegende Ole, jede Formel ist gemacht, um Regen, Sonne und Zeit zu trotzen. Fur Zaune, Terrassen, Gartenhauser, fur alles, was drau?en steht und Charakter hat. Bondex halt, was Natur verspricht – Bestandigkeit mit Herz und Hand.

Hallo bei https://das-bosca.de/. Die Auswahl reicht von elektrischen Fondues uber Raclette-Sets bis zu Pizza- und Schneidewerkzeugen. Fondue- und Raclette-Topfe sitzen stabil auf dem Tisch, die Messer schneiden Kase und Fleisch prazise, Boards tragen Snacks oder Tapas. Grillplatten, Pizzaheber und Pizzasteine erweitern die Moglichkeiten, alles aus robustem Holz und Edelstahl, einfach zu handhaben, direkt auf dem Tisch einsetzbar. Jede Komponente fuhlt sich vertraut an und erleichtert das gemeinsame Essen.

Hi, I do believe this is a great website. I stumbledupon it 😉 I’m going to revisit yet again since I book-marked it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may you be rich and continue to help others.

Appreciate this post. Will try it out.

Lock and Love creates jewelry inspired by love and connection, perfect for special moments. Their designs include locks, keys, and heart motifs to symbolize affection. Discover their collection at https://thelockandlove.com.

Aablexema’s accessories and fashion items stand out for their originality and quality. Perfect for those who want to add personality to their look. Check out their offerings at https://theaablexema.com.

Moonet’s collection focuses on casual pieces with clean lines and comfortable fabrics. Ideal for those who appreciate simple, versatile style. Discover the range at https://themoonet.com.

Hallo an alle, die den Geruch von Farbe und den Klang klickender Teile lieben. https://das-aoshima.de/ erschafft kleine Wunder aus Plastik – vom kultigen Knight Rider bis zum legendaren DeLorean. Turen offnen sich, Lichter glimmen, Formen erwachen. Jedes Modell erzahlt Geschichten von Geschwindigkeit, Kino und Kindheit, eingefangen im Ma?stab 1:24.

I blog frequently and I truly appreciate your information. This article has really peaked my interest. I will take a note of your blog and keep checking for new information about once a week. I opted in for your Feed as well.

Hallo bei https://dasdasique.de/. Die Palette vereint verschiedene Rouge- und Puderfarben, die sich leicht auftragen lassen. Lippenbalsame in Beerentonen oder sanften Pfirsichnuancen geben Feuchtigkeit und Glanz. Concealer-Paletten gleichen Hauttone aus und decken punktuelle Unregelma?igkeiten ab. Alle Produkte gleiten sanft, lassen sich mischen und wirken naturlich, vegan hergestellt, fur unkomplizierte Anwendung jeden Tag.

Gates of Olympus free play máte možnost otestovat ihned také v casinu Betor. Pokud si zde budete chtít zahrát o reálné peníze, stačí se zaregistrovat. Na nové hráče pak čeká štědrý uvítací bonus 200 free spinů na legendárním automatu Hunter’s Dream 2 a bonus za vytvoření dočasného konta ve výši 50 Kč. Hrajte zodpovědně a pro zábavu! Zákaz účasti osob mladších 18 let na hazardní hře. Ministerstvo financí varuje: Účastí na hazardní hře může vzniknout závislost!Využití bonusů je podmíněno registrací u provozovatele – informace zde. Na EncyklopedieHazardu.cz nejsou provozovány hazardní hry ani zde neprobíhá zprostředkování jakýchkoliv plateb. Jedním z hlavních lákadel online automatů je možnost hrát za skutečné peníze i zdarma. K tomu přispívá i funkce demo režimu, která umožňuje hráčům vyzkoušet si hru, aniž by museli vložit skutečné peníze. Na Fairspin můžete snadno přecházet mezi hraním pro zábavu a hraním za skutečné peníze, což je ideální pro nové hráče i pro ty zkušenější, kteří se chtějí seznámit s novými automaty.

https://dumbschool.com/recenze-hry-tiki-taka-v-online-casinu-pro-hrace-z-ceska/

Hodnocení online slotu Gates of Olympus: 9,5 10 V současnosti se můžeme setkat s širokou nabídkou online automatů s různými funkcemi, zajímavými bonusy a poutavou grafikou. Mohou zaujmout motivem, příběhem, ale také oblíbenými progresivními jackpoty. Celkově vzato jsou automaty nedílnou součástí světa hazardu. Portfolio automatů se navíc neustále rozšiřuje, inovuje a přináší nové možnosti hraní. Osobně tuto hru doporučuji. Podlé mého od společnost Pragmatic není lepší hry. Možná ještě psí boudičky, tedy Dog House Megaways… Na bóžkovi se mi mimo jiné líbí také hezký hudební podklad. Zahrajte si tuto hru také a uvidíte, jak vás dokáže vtáhnout. Diamanty, srdíčka a další naleštěné výherní symboly vám zaručují bohatou grafickou podívanou. Jakmile chytíte kdekoli na herní obrazovce alespoň 8 stejných symbolů, vyhráváte. Čím více jich nasbíráte, tím vyšší je výhra. Po každé výherní kombinaci navíc dojde k propadu již vyplacených kombinací a napadají nové, další možné výherní symboly. Symbol SCATTER navíc stačí chytit jen 4x a dostanete k výhře 15 otočení zdarma, stejně jako tomu je ve hře Sweet Bonanza, kterou si představíme níže.

Hallo! Bei https://das-aulos.de/ zeigt sich, wie Sopran- und Altblockfloten klingen und sich greifen lassen. Jede Flote fuhlt sich solide an, die Tone sind gleichma?ig und klar. Die Instrumente gleiten angenehm durch die Finger, lassen sich einfach stimmen und reinigen. Spieler erleben direkt, wie sich Musik muhelos formen lasst.

Hallo! Bei https://das-uking.de/ stehen LED Moving Heads bereit, die RGBW-Farben mischen und sich flexibel ausrichten lassen. Nebelmaschinen erzeugen dichte, sichtbare Effekte, die das Licht sichtbar machen. LED Bars, Wall Washer und Schwarzlicht erganzen die Ausstattung. Die Gerate lassen sich einfach bedienen, reagieren auf Musik und bringen Buhnen, Partys oder Clubabende lebendig zum Leuchten.

pg slot

แพลตฟอร์ม TKBNEKO ทำงานเป็นระบบเกมออนไลน์ ที่ วางระบบโดยยึดการใช้งานจริงของผู้เล่นเป็นแกนหลัก. หน้าเว็บหลัก แสดงเงื่อนไขแบบเป็นตัวเลขตั้งแต่แรก: ขั้นต่ำฝาก 1 บาท, ถอนขั้นต่ำ 1 บาท, เวลาฝากประมาณ 3 วินาที, และ ยอดถอนไม่มีเพดาน. ตัวเลขเหล่านี้กำหนดภาระของระบบโดยตรง เพราะเมื่อ ตั้งขั้นต่ำไว้ต่ำมาก ระบบต้อง รับรายการฝากถอนจำนวนมากที่มียอดเล็ก และต้อง ประมวลผลแบบเรียลไทม์. หาก เครดิตเข้าไม่ทันในไม่กี่วินาที ผู้ใช้จะ กดซ้ำ ทำให้เกิด รายการซ้อน และ ดันโหลดระบบขึ้นทันที.

การฝากผ่าน QR Code ตัดขั้นตอนการกรอกข้อมูลและการแนบสลิป. เมื่อผู้ใช้ สแกนคิวอาร์ ระบบจะรับสถานะธุรกรรมจากธนาคารผ่าน API. จากนั้น backend จะ ผูกธุรกรรมเข้ากับบัญชีผู้ใช้ และ เติมเครดิตเข้า wallet. หาก API ตอบสนองช้า เครดิตจะ ไม่ขึ้นตามเวลาที่ประกาศ และผู้ใช้จะ ถือว่าระบบไม่เสถียร. ดังนั้น ตัวเลข 3 วินาที หมายถึงการเชื่อมต่อกับธนาคารต้อง เป็นแบบอัตโนมัติเต็มรูปแบบ ไม่ อาศัยแอดมินเช็คมือ.

การเชื่อมหลายช่องทางการจ่าย เช่น KBank, Bangkok Bank, KTB, Krungsri, SCB, CIMB Thai รวมถึง ทรูมันนี่ วอลเล็ท ทำให้ระบบต้อง จัดการ webhook หลายแหล่ง. แต่ละธนาคารมีรูปแบบข้อมูลและเวลาตอบสนองต่างกัน. หากไม่มี โมดูลแปลงข้อมูลให้เป็นมาตรฐานเดียว ระบบจะ เช็คยอดไม่ทัน และจะเกิด ยอดค้างระบบ.

หมวดเกม ถูกแยกเป็น สล็อตออนไลน์, คาสิโนสด, กีฬา และ เกมยิงปลา. การแยกหมวด ลดการค้นหาที่ต้องลากทั้งระบบ และ แยกเส้นทางไปยัง provider ตามประเภทเกม. สล็อต มัก เชื่อมต่อผ่าน session API ส่วน เกมสด ใช้ สตรีมแบบสด. หาก หลุดเซสชัน ผู้เล่นจะ หลุดจากโต๊ะทันที. ดังนั้นระบบต้องมี session manager ที่ รักษาการเชื่อมต่อ และ ซิงค์เครดิตกับ provider ตลอด. หาก ซิงค์ล้มเหลว เครดิตผู้เล่นกับผลเกมจะ ไม่ตรงกัน.